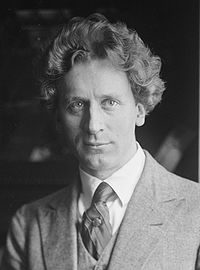

Percy Grainger

| Percy Aldridge Grainger | |

|---|---|

Percy Aldridge Grainger (1882–1961) |

|

| Born | George Percy Grainger 8 July 1882 Brighton, Victoria, Australia |

| Died | 20 February 1961 White Plains, New York, United States |

| Cause of death | Prostate cancer |

| Resting place | Adelaide, Australia West Terrace Cemetery |

| Residence | White Plains, New York, United States |

| Nationality | Australian, later American |

| Education | Hoch Conservatory, Frankfurt |

| Occupation | Composer/Pianist |

| Known for | "Country Gardens", "Irish Tune from County Derry," "Molly on the Shore," "Lincolnshire Posy" |

| Spouse | Ella Viola Brandelius Ström |

| Parents | John Harry Grainger Rose Annie Aldridge |

George Percy Grainger (8 July 1882 – 20 February 1961) was an Australian-born composer and pianist who worked under the stage name of Percy Aldridge Grainger.

Contents |

Early life and career

Grainger's father, John Harry Grainger, was a successful and talented architect who grew up in France and was educated in a monastery school in Yvetot. He emigrated from London, England in 1876. John Grainger's business partner and best friend was David Mitchell, the father of Nellie Melba. Mitchell was determined to prevent Nellie from taking up singing as a career and John Grainger is credited with encouraging her singing. He maintained a close friendship with Nellie and later designed her house, "Coombe Cottage", in 1912.[1]

Grainger's mother, Rose (née Rosa Annie Aldridge; 3 July 1861, Adelaide – 30 April 1922, New York City), was the daughter of George Aldridge and Sarah Jane Aldridge (née Brown), hoteliers from Adelaide, also of English immigrant stock.

Grainger was born in Brighton, a suburb of Melbourne. His mother had contracted syphilis from her husband early in the marriage; after Percy's birth she refused to touch him until he was five years old, for fear of passing it on to him. In 1890, Grainger's father took a sea voyage in order to improve his health. This coincided with the end of his marriage: he was never to live with his wife and child again. Rose and Percy remained in Melbourne and the two of them visited Rose's family in Adelaide from time to time but they never moved back there. John returned to Adelaide and never rejoined his family.[2] In 1903, while he was touring New Zealand, Rose wrote to Grainger that his father had visited her in Adelaide and was travelling to Rotorua for treatment, warning him not to touch his father if they should meet. On a train to Rotorua, Grainger did run into his father and later wrote about the meeting to a friend. Grainger said he was pleased to meet him and that his father had explained "his dubious past" and ended the letter with "How I hope one day to earn such suffering as both my elders have gone thro!!(sic)".[3] Grainger continued to correspond and see him occasionally and from 1905 he began supporting his father financially. His father died in 1917 of tertiary syphilis.

Grainger's mother was domineering and possessive, although cultured. While pregnant, she allocated time each day to stare at a statue of a Greek god in the belief it would pass some of its qualities to her child. A striking individual with blue eyes and brilliant orange hair, Percy gave his first public performance at the age of 12, and critics hailed him as a new prodigy. Due to taunts about his appearance Grainger spent less than three months in school and after refusing to return was home schooled by his mother. She was a strict disciplinarian, but ironically her tombstone reads, "Wise, wonderful, devoted, angelic mother." Grainger excelled in languages and his correspondence shows he was fluent in 11 foreign languages including Icelandic and Russian.[4]

His mother took him to Europe in 1895 to study at Dr. Hoch's Conservatory in Frankfurt. There he displayed his talents as a musical experimenter, using irregular and unusual meters. He belonged to the Frankfurt Group, a circle of composers who studied at the Hoch Conservatory in the late 1890s. Fellow-students included Cyril Scott, Henry Balfour Gardiner, Norman O'Neill and Roger Quilter. Grainger himself did not believe in such a concept as musical talent and attributed his career to his mother's influence. During his time in Frankfurt, he lost the tip of an index finger while working on a bicycle chain. Although Grainger himself hoped he would have to give up concerts and be able to concentrate on composing, his performance ability was not affected by this handicap.

Grainger was an innovative musician who anticipated many forms of twentieth century music well before they became established by other composers. As early as 1899 he was working with "beatless music", using metric successions (including such sequences as 2/4, 2½/4, 3/4, 2½/4). His use of chance music in 1912 predated John Cage by forty years, and he wrote "unplayable" music for player piano rolls 20 years before Conlon Nancarrow.

From 1901 to 1914, Grainger lived in London, where he befriended and was influenced by composer Edvard Grieg. Grieg had a longstanding interest in the folk songs of his native Norway, and Grainger developed a particular interest in the folk songs of rural England. The interest moved to active collecting after he heard Lucy Broadwood's lecture on folksong collecting in 1905. In 1906, Grainger hiked around Britain making field recordings of these folk songs on Edison wax cylinders, the first to make such recordings in Britain.[5] During this period, Grainger also wrote and performed piano compositions that presaged the forthcoming popularization of the tone cluster by Leo Ornstein and Henry Cowell.

Grainger's energy was legendary. In London, he was known as "the jogging pianist" for his habit of racing through the streets to a concert, where he would bound on stage at the last minute because he preferred to be in a state of utter exhaustion when playing. After finishing a concert while touring in South Africa, he then walked 105 km to the next, arriving just in time to perform. When travelling by ship on tour, he spent his free time shovelling coal in the boiler room. He gave well over 3,000 concerts as a pianist or conductor.

In 1910, Grainger began designing and making his own clothing, ranging from jackets, to shorts, togas, muumuus and leggings, all made from towels and also intricate grass and beaded skirts. The clothing was not just for private use but he often wore it in public. He also designed a crude forerunner of the modern sports bra for his Danish sweetheart, Karen Kellerman, née Holten.

Grainger moved to the United States at the outbreak of World War I in 1914, due to growing pressure on him to enlist in the military, which he refused to do because of his disapproval of modern warfare. His 1916 piano composition In a Nutshell is the first by a classical music professional in the Western tradition to require direct, non-keyed sounding of the strings—in this case, with a mallet—which would come to be known as a "string piano" technique. When the United States entered the war in 1917, he realized that he could not remain a passive observer forever, so he enlisted into a United States Army band, playing the oboe and soprano saxophone, and spent the duration of the war giving dozens of concerts in aid of War Bonds and Liberty Loans, as well as in aid of the American Red Cross. Also during the year 1917, he was elected an honorary member of Phi Mu Alpha Sinfonia music fraternity. In 1918, he became a naturalized citizen of the United States.

Career success

Grainger's piano solo Country Gardens became a smash hit, securing his reputation as a remarkable composer, although Grainger grew to detest the piece. With his newfound wealth, Grainger and his mother settled in the suburb of White Plains, New York after the war. Rose Grainger's mental and physical health, however, was in decline. She committed suicide in 1922 by jumping from the building where her son's manager, Antonia Sawyer, had an office.[6] This ended an intimate relationship, which many had incorrectly assumed to be incestuous. After his mother's death, he found a letter that she had written to him the day before she took her life, explaining her state of mind, which she explained was caused by accusations of incest. Grainger kept it in a cylinder he wore around his neck for many years. He later compiled an album containing photos of his mother (including several of her in her coffin), and had thousands of copies made and distributed to friends.

In the same year, he traveled to Denmark, his first folk-music collecting trip to Scandinavia (although he had visited Grieg there in 1906). The orchestration of the region's music would shape much of his finest output.

By 1925, Grainger was financially secure. He was now earning $5,000 (2007:$58,692) a week for performances and charging up to $200 (2007:$2,348) an hour for private lessons. In November 1926, Grainger met the Swedish artist and poet Ella Viola Ström, and fell in love at first sight. Their wedding took place on 9 August 1928 on the stage of the Hollywood Bowl, following a concert before an audience of 20,000, with an orchestra of 126 musicians and an a cappella choir, which sang his new composition, To a Nordic Princess, dedicated to Ella.

In December 1929, Grainger developed a style of orchestration that he called "Elastic Scoring". He outlined this concept in an essay that he called, "To Conductors, and those forming, or in charge of, Amateur Orchestras, High School, College and Music School Orchestras and Chamber-Music Bodies".

In 1932, he became Dean of Music at New York University, and underscored his reputation as an experimenter by putting jazz on the syllabus and inviting Duke Ellington as a guest lecturer. Twice he was offered honorary doctorates of music, but turned them down, explaining, "I feel that my music must be regarded as a product of non education".

Grainger often appeared as a guest conductor of the Goldman Band, which gave the first complete performance of Grainger's masterpiece Lincolnshire Posy in the summer of 1937. He was said to have never driven an automobile, and instead used a bicycle, even driving it the 25-mile distance from his White Plains home to the Goldman Band concerts at Central Park in New York City.

Declining career and death

In 1940, the Graingers moved to Springfield, Missouri, fearful that their home situated on the eastern seaboard would be vulnerable to enemy attack, from which base Grainger again toured to give a series of army concerts during the Second World War.

In 1941, Percy Grainger toured the State of Minnesota with the Gustavus Adolphus College Concert Band under the direction of his close friend Frederic Walter Hilary. During these concerts Grainger shared the piano with Joyce Virginia Westrom of Cambridge, Minnesota, who was later to marry Hilary. Several of these concerts were given to raise money for the war efforts.

However, the gradual decline in popularity of his music after the war hit his spirits hard. To get his music heard, he offered to play for little or no fee, which resulted in his income from concerts drying up. He last appeared in public at Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire in 1960.

In his last years, working in collaboration with physicist Burnett Cross, Grainger invented the "Free Music Machine", which was the forerunner of the electric synthesizer.

Although still physically fit into his 60s, he spent his last years suffering pain from abdominal cancer which had spread, despite a number of operations, from prostate cancer diagnosed in 1953.[7] Grainger died in White Plains, New York in 1961 and he was buried in West Terrace Cemetery, Adelaide, South Australia.

His personal files and records have been preserved at The Grainger Museum in the grounds of the University of Melbourne, the design and construction of which he oversaw. Restoration of the museum was completed in December 2009,[8] and conservation efforts continue. [9]

Many of his instruments and scores are located at the Grainger house in White Plains, New York, now the headquarters of the International Percy Grainger Society, under the aegis of archivist Stuart Manville. Manville wed Percy's widow Ella in 1972 and became a widower upon her death in 1979.

He is remembered in the name of Grainger Circuit, in the Canberra suburb of Melba.

Free Music and Grainger’s machines

In Australia, Grainger is remembered chiefly for his musical innovations and for what he called “Free Music”. He first conceived his idea of Free Music as a boy of 11 or 12. It was suggested to him by observing the waves on Albert Park Lake in Melbourne. Eventually he concluded that the future of music lay in freeing up rhythmic procedures and in the subtle variation of pitch, producing glissando like movement. These ideas were to remain with him throughout his life, and he spent a great deal of his time in later years developing machines to realise his conception

Free Music is melodic (polyphonic), making use of long, sustained tones capable of continuous changes in pitch. No traditional form of notation exists to describe it in detail. Grainger's own scores were originally notated on graph paper, with an individual trace for both the pitch and dynamic changes of each note. Free Music assumes a moving tone, precluding any harmonic stability and working with it is difficult since almost every basic assumption about musical relationships and method must be ignored. Free Music requires the abolition of the scale and its replacement by a controlled continuous glide.

Grainger resorted to the use of machines because human performers on traditional instruments were not capable of producing the wide range of "gliding tones" with the necessary control over minute fluctuations of pitch. The machines were not intended as performance devices. Rather, they were designed to allow Grainger to hear the sounds he composed. He insisted on hearing his compositions before allowing them to be published, and often went to extraordinary lengths to achieve this.

His most famous machine is the "Hills and Dales" machine, described by Grainger as the "Kangaroo Pouch method of synchronising and playing eight oscillators" (on display in the Grainger Museum). Commonly known as the “Kangaroo Pouch machine”, it consists of a large wooden frame approximately eight feet tall, housing upright rotating turrets left and right (the "feeder' and "eater" turrets) and between which a large paper roll is wound. This roll consists of three layers: a main paper roll 80 inches high, across which eight smaller horizontal strips of paper (or subsidiary rolls) are attached front and back. The top edges of these subsidiary rolls are cut into curvilinear shapes (the hills and dales) and attached to the main roll at their bottom edges, each forming a type of "pouch". As the turrets are rotated clockwise, the undulating shapes cut into the rolls move from right to left.

Eight valve oscillators are mounted onto the wooden frame, four at the front and four at the back, as are eight amplifiers. The pitch controls of the oscillators are attached to levers, connected at the other ends to circular runners, or spools, which "ride" moving rolls. The volume controls of the amplifiers are operated in the same way. Thus, the pitch of the oscillators, and the volume of the amplifiers, can be accurately controlled by carefully cutting shapes into the paper rolls. The large size of the machine is necessary to maintain accuracy of pitch control. Because the valves changed characteristics as they aged, the machine needed to be recalibrated after around three hours of use.

Grainger’s final machine was perhaps the most sophisticated. It too worked on the principle of a moving roll, but this time made of clear plastic. A row of spotlights projected light beams through the plastic roll and onto an array of photocells, which in turn controlled the pitch of the oscillators. The undulating shapes cut into the paper rolls of the Kangaroo Pouch machine were now simply painted onto the plastic roll with black ink. The circuitry for this machine was transistorised, lending a stability which could not be achieved with the use of valves. The machine was lost in the 1970s while being transported from Grainger's home in White Plains to the Grainger museum in Melbourne.

Personality

Grainger was a vegetarian who was not particularly fond of vegetables, and lived variously on nuts, boiled rice, wheatcakes, cakes, bread and jam, ice cream and oranges.[10]

Grainger was a sado-masochist, with a particular enthusiasm for flagellation,[11] who extensively documented and photographed everything he and his wife did. His walls and ceilings were covered in mirrors so that after sessions of self-flagellation he could take pictures of himself from all angles, documenting each image with details such as date, time, location, whip used, and camera settings.[10]

He gave most of his earnings from 1934–1935 to the University of Melbourne for the creation and maintenance of a museum dedicated to himself. Along with his manuscript scores and musical instruments, he donated the photos, 73 whips, and blood-soaked shirts.[12] Although the museum opened in 1935, it was not available to researchers until later.

He was a cheerful believer in the racial superiority of blond-haired and blue-eyed northern Europeans. This led to attempts, in his letters and musical manuscripts, to use only what he called "blue-eyed English" (akin to Anglish and the 'Pure English' of Dorset poet William Barnes) which expunged all foreign (i.e., non-Germanic) influences. In Grainger's writings, a composer was a "tone-smith" who "dished up" his compositions and a piano was a "keyed-hammer-string". He hated Italian terms in music scores; "poco a poco crescendo molto" became "louden lots bit by bit".

This bias was not consistently applied though: he was friends with and an admirer of Duke Ellington and George Gershwin, and also gave regular donations to African-American causes. Grainger eagerly collected folk music tunes, forms, and instruments from around the world, from Ireland to Bali, and incorporated them into his own works. Furthermore, alongside his love for Scandinavia was a deep distaste for German academic music theory; he almost always shunned such standard (and ubiquitous) musical structures as sonata form, calling them "German" impositions. He was ready to extend his admiration for the wild, free life of the ancient Vikings to other groups around the world, which in his view shared their way of life, such as the ancient Greece of the Homeric epics.

Other departures from the common norms of the time included never ironing his shirts and wearing the same clothes for days. He once said "concert audiences can't tell the difference". While in America, he was twice arrested for vagrancy due to his dress. In his later years, when he scavenged in rubbish bins in the middle of the night for parts to make musical instruments, he dressed in his best clothes for the task.

Grainger was a stout believer in natural forces and felt that the summer months were meant to be hot and the winter months were meant to be cold. Thus in winter he slept naked with his bedroom windows open, while spending the stifling summer evenings adorned in heavy wool.

Piano roll performances

Throughout the 1920s, Grainger recorded numerous live-recording player piano music rolls for the Aeolian Company's "Duo-Art" system, all of which survive and can be heard.

Amongst these is a complete rendering of Grieg's Piano Concerto and a recently unearthed performance of music from "The Warriors". Grainger's own Duo-Art grand pianola can still be seen at the Grainger Museum, complete with Grainger's music machine experimental modifications.

Dramatic portrayals

Grainger's life has been portrayed in a number of dramas, notably Rob George's 1982 stage play, Percy & Rose, which was later used for a loose adaptation in the 1999 film Passion. Featuring Richard Roxburgh as Grainger and Barbara Hershey as his mother, it was co-written by Rob George and John Bird, author of the 1999 Oxford University Press biography of Grainger.[13] The screen play for Passion was written by George Goldsworthy, Peter Goldsworthy, and Don Watson.

His character also appeared in the 1968 Ken Russell film Song of Summer, about the final years of his friend Frederick Delius. He was played by David Collings.

Notable works

|

|

Notes and references

- ↑ Percy Grainger by John Bird ISBN 0198166524 Pg 11

- ↑ Percy Grainger by John Bird (1999) ISBN 0198166524 Pg 9

The family doctor told Rose that it would have been kinder if her husband had shot her dead. Her fear of the disease lasted throughout her life and was the main reason she refused to accept her husband after he returned from his trip. - ↑ Percy Grainger by John Bird ISBN 0198166524 Pg 97

- ↑ Official Percy Grainger website

- ↑ D. de Val, 'Lucy Broadwood and Folksong', in Music and British Culture, 1785–1914, ed. C. Bashford and L. Langley (Oxford: OUP, 2000), 341–-66, on Grainger, 355–-64.

- ↑ Portrait of Percy Grainger, (eds.) Malcolm Gillies and David Pear (Eastman Studies in Music), University of Rochester Press, Rochester, NY, 2002, pp.99–103)

- ↑ The All-Round Man: Selected Letters of Percy Grainger, 1914–1961, ed. Malcolm Gillies, David Pear, Oxford University Press, 1994, ISBN 0198163770.

- ↑ http://www.lovellchen.com.au/news.aspx

- ↑ http://www.lib.unimelb.edu.au/collections/grainger/museum/closed.html

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Percy Grainger, John Bird, Oxford University Press, 1999, ISBN 0198166524

- ↑ http://www.lib.unimelb.edu.au/collections/grainger/collection/#lust

- ↑ www.grainger.unimelb.edu.au

- ↑ "Passion (1999)". ImDb. http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0148583/fullcredits#writers. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

External links

- The International Percy Grainger Society

- The Percy Grainger Society

- The Grainger Ensemble – archived website for a Melbourne chamber orchestra

- Grainger on Australian Music Centre site

- The Grainger Wind Symphony, an Australian Wind Symphony honouring Percy Grainger

- The Grainger Museum at the University of Melbourne, Australia

- Percy Grainger in MusicAustralia

- Works by Percy Grainger at Project Gutenberg

- Percy Grainger at the Internet Movie Database

- Percy Grainger at the National Film and Sound Archive

- The Free Music Machines of Percy Grainger Rainer Linz

- Performance of Youthful Rapture

- Performance of Brigg Fair

- Grainger, George Percy Biography from the Australian Dictionary of Biography: Online Edition